|

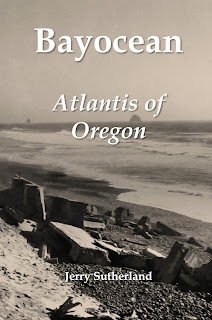

| Bayocean Natatorium. BOB95, Tillamook County Pioneer Museum. |

|

| Seaside's first natatorium was the two-story part of the Turnaround Building, on the right (south) side of this photo. The Trendwest Resort stands there now. Seaside Museum image. |

T. Irving Potter tried to regain lost ground by making his natatorium larger than the rest and installing a wave generator he invented. The first of its kind had been used at the outdoor Bilzbad baths in Radebeul, Germany since 1911, but Bayocean's was the first indoor application. Unfortunately, it was difficult to maintain and was offline more often than it worked. The rest of the structure also required constant maintenance, which is why it lost money every year it was open.

When

the Rockaway Natatorium was finished in 1926, folks started going there instead of Bayocean because it was much easier to get to and better maintained. As a result, the Tillamook-Bayocean Company (a group of local businessmen) could find no one to lease Bayocean's natatorium, so it stayed closed in 1927 and never reopened to the public. In 1932, erosion that had been moving the waves closer for a decade undercut the west wall during a winter storm, causing it to collapse. The building was later deconstructed and used to build the Sherwood House on Cape Meares. Bayocean Natatorium competitors all lasted longer, but the only one still standing is the second one built at Seaside, which now hosts the Seaside Aquarium.

|

| BOB 68, Tillamook County Pioneer Museum. |

See the Index for more articles that might be of interest.

%20&%20Post%20Office.jpg)

%20postmaster..jpg)

,%20no%20pricing.jpg)